[Written on 26 July]

It’s three years today since my mother died, joining my father in death and leaving my brothers and I alone, and me the oldest in the family as well as the matriarch. That came a hell of a realisation, I can tell you.

My mother planned to live until she was in her nineties. But I knew this was unlikely.

Deeply suspicious of the medical establishment, and rightly so given her woeful treatment by male gynaecologists who happily stole her fertility and thrust her into early menopause, she refused to deal with them.

Then when she was forced to, she trusted another male doctor who once again let her down, ironically because he gave her what he thought she wanted even though it meant an earlier than necessary death, which I know she did not want at all. But would he listen? No. He would look at me like some interfering busy body as she told to him time and again the lies she told herself.

But that’s all in the past. What is it that I miss about her today, a day of many challenges?

Perhaps I miss that I have no one and nowhere to go to.

Not that my mother ever understood me or my problems, or was someone I could easily turn to. I could in theory, but in reality I whenever I tried I found myself feeling more alone than ever, more unrecognised with every attempt.

I don’t blame my mother for her remoteness. Abandoned by her father in her teens in the worst kind of way, reviled by a jealous and competitive mother, and a survivor of all sorts of childhood travesties including during World War II, she didn’t let that overcome her. Instead she immigrated, had a family and created her dream of being a psychologist.

I admire and respect that and am filled with awe for her.

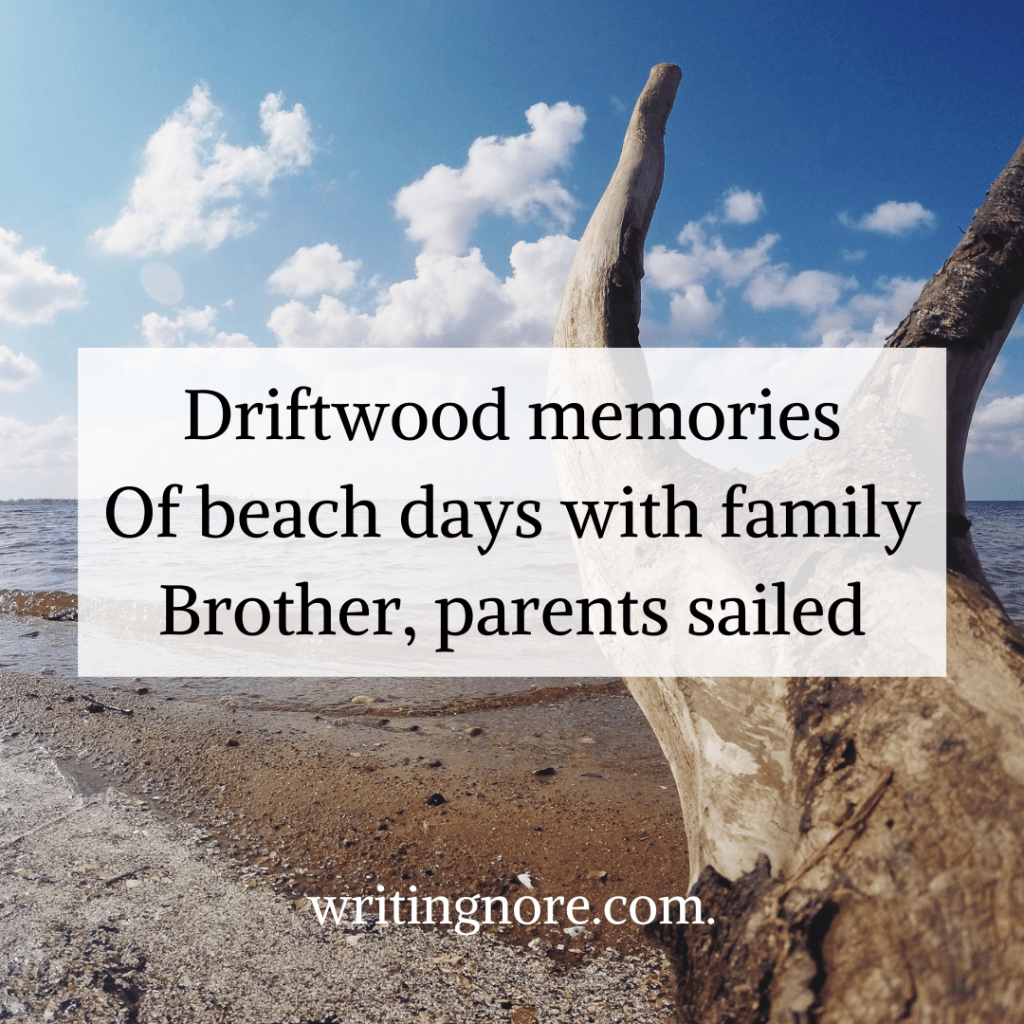

She could have been a bitter and angry person, she could have inflicted upon us what was done to her. But she wasn’t and she didn’t. She chose to help people. But with me, we were forever ships in the other’s night, reaching out but finding the other too far away to grab hold of. I could not find her being behind her mask of survival and control.

Perhaps what I miss today – and what I’ve continued to struggle to come to terms with these three years – is what we were not and what we can now never be. Her once soft belly and warm full breast of the mother of my dreams would never be realised. All those times I called her up and fell mute when she failed to hear me. That time, days before her death, when I cried into the phone that I never truly felt her love other than as some intellectual exercise. Finally she convinced me it was there, and for some moments it finally was laid bare.

Right now I would settle for even for five minutes of the frustration with her. I would get in my car to be with her, a person who despite it all, welcomed me no matter what.

So perhaps what I really miss is not just her strangled kind of love, but that her death has forced me to grow up. Perhaps I miss being a child. Her death has indeed forced me to be alone at a time when I could very much do with an escape.

And there it is. There is no escape. There is only, and has only ever been, me. And that is the greatest realisation and hurt right there. That she dared to leave me. That she could never rescue me. That I am alone, just as I always was. And neither she nor anyone was ever going to be able to allay that truth.

Maybe there is a part of me too that regrets those struggles we had, who wished I wasn’t so busy with my life during her middle years, who wished I had been more generous with my time and made my mother more welcome, who was less driven mad by her incessant self talk.

Perhaps there is part of me also who, with time, has imagined she could have been different, that she could have changed. But the truth is that no matter how hard I tried, she was never going to be different. She could never step into that hopeful void I made for her to step into.

So as much as all of that, and in the very end, I simply miss my mother. Bravo, mother. Bravo. I love and miss you no matter it all.