Most nights from my 3rd-storey bedroom window in my semi-rural Sunshine Coast home, I look out and see a strangely long and exceedingly bright star. Except it isn’t a star – it’s reputedly Elon Musk’s satellite.

From the moment I learned this I felt watched over, as if I didn’t already know that feeling from the devices and apps I’m aware track my movements, opinions, conversations, shopping habits and more.

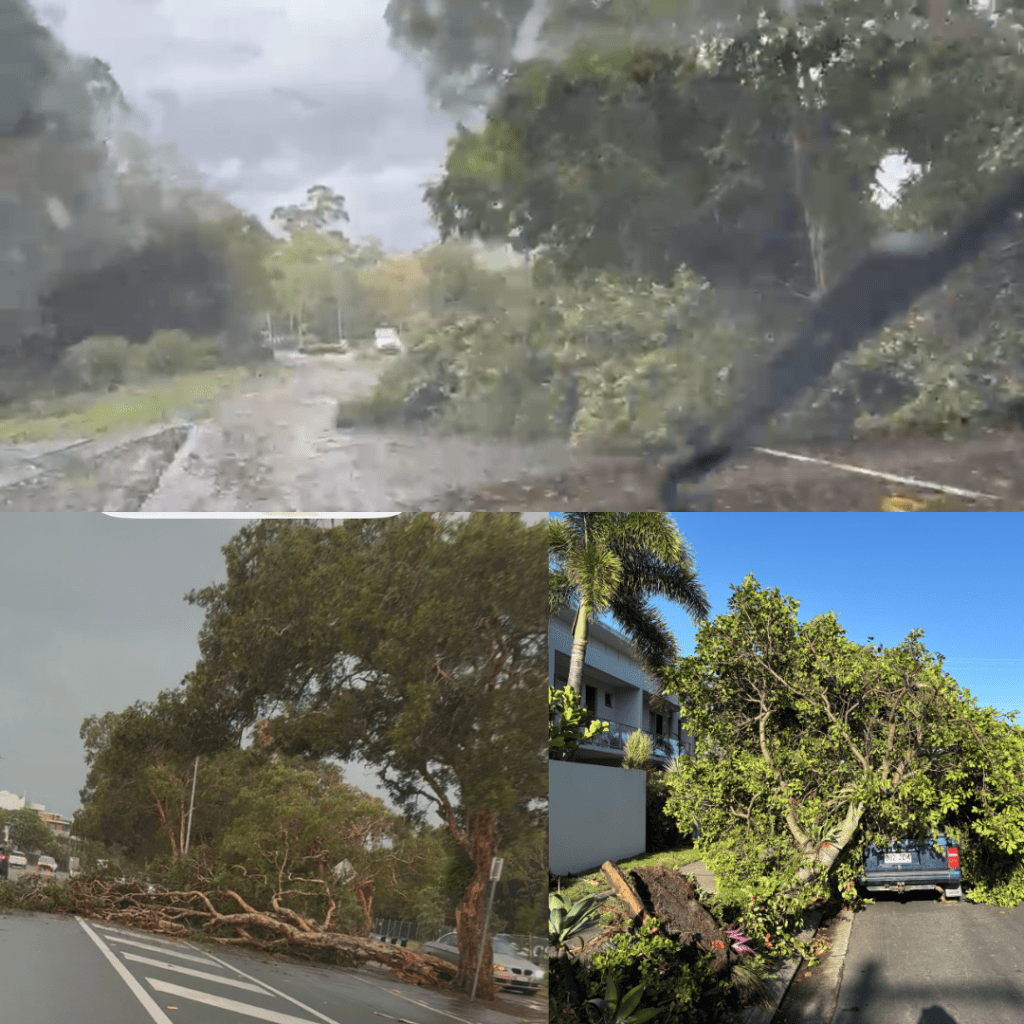

So it was interesting when a surprise storm hit my little town with winds of 150+ km per hour, felling entire trees, launching our balcony furniture 200 metres away into a neighbour’s yard, peeling our roof back, and picking up my large potted tree and dumping it 10 metres away as though it was flotsam.

I was out at a local appointment, and once the lightning stopped began to make my way through the debris, scattered shop signs and collapsed trees blocking the roads. My husband said at one point our windows were so buckled inwards with the force of the wind that he was certain they would give way. (Oh the irony after all our preparations earlier this year with the massive cyclone that never eventuated.)

Once the wind and rain had subsided, we began cleaning up the mess.

But it’s a different aftermath that was perhaps more disturbing.

We lost power, NBN and all communications for two days in my street, others for one or three days.

My first thought was how unsafe I felt without a phone, radio or satellite to use in an emergency or just to check if my nearby family were safe. Unless you have a satellite, everything else is digital these days, so when the network goes, everything goes. How vulnerable we’ve made ourselves.

My second thought was that because I work 100% online I was unable do that, or in other words, I couldn’t earn a living. I had to drive half and hour away to cancel and rebook consults. Not much of a disaster in the scheme of things, but given so many of us work from home I understood how this could become a greater problem in the future.

This leads me to my third realisation, which was that more frequent and unexpected weather events is the new normal, and that I needed to be more prepared. Climate change is real now, and I need a sat phone, better emergency rations and cooking gear. We already have a solar battery, which kept our lights on and food cold, plenty of stored water, and I have a first aid kit and updated training.

And then, somewhat shamefully – and even more alarming – was the observation of how irritable, bored and empty I felt after 12 hours of not having instant access to everything I normally entertained and calmed myself with, from social media, games and streaming to the ability to message my family and friends.

How had I lived happily for years without these props and fillers? How had a shared free-to-air TV, books, pen and paper, music, a landline, and the odd hobby ever been enough?

While this seems petty given the bigger issues of climate change, safety and my ability to earn money, the loss of communications brought home to me how modern technology had changed my brain. I was ashamed to admit that I too had become addicted, craving the next dopamine hit, and using it as a crutch to fill my quieter moments and block out the the stuff of life I’d rather not face.

So what is missing from my life that I was drawn to this addiction? What must I now rebuild and replenish?

I thought about this long and hard and decided that for me, creativity is the antithesis and antidote to the mind-numbing hypnosis of modern technology. Instant entertainment is self-fulfilling vicious cycle that numbs me out while making me want more of it to rouse my emotions and lift me up again. My former overuse is a pleasure-seeking road to hollowness. We cannot eat sugar all day and expect no consequences.

I’m already reading more books, I’m planning my next novel and restarting this blog (without the use of AI), I don’t check my social media often. In fact, I’m toying with getting rid of my social media accounts altogether but … business. I also ensure I sit in silence for 10 minutes every day, walk more without my phone, and if I feel bored, I welcome it and see what revelation or idea might surface.

What about you and our instant online life?