Wise words from a man who, against all odds, shaped destiny. Fight for your writing.

Wise words from a man who, against all odds, shaped destiny. Fight for your writing.

When writing fiction, creative non-fiction and even good non-fiction, writing in the active voice is usually best. Here’s a quick summary of why.

Active Voice

Using the active voice means the subject* of your sentence does the action. In other words it’s someone or something doing something rather than it being done to them. Active sentences are more alive because they’re more direct, succinct and closer. They draw you in.

[*The subject is the who/thing that’s doing something. It’s usually a noun like Jenny or The dog or a noun phrase. It’s the beginning and main focus of the sentence. The object is the what is being done and follows the verb.]

Passive Voice

Using the passive voice means the subject receives the action. The subject is being acted upon by an outside force. Passive sentences use more words, can be vague and often lead to a tangle of prepositional phrases (which begin with at, in, about, from, with, by).

The passive voice is often used in bureaucratic or scientific writing to take the focus away from individual beliefs or responsibility and towards bureaucratic responsibility or research data. While there are times when the passive voice may be appropriate, by design it’s not engaging writing.

Examples:

Active or Passive Voice

In most writing, we prefer the active voice to be prominent. It’s more direct and promotes stronger verbs. Verbs and nouns bring sentences alive and give them power, which makes readers keep turning the page. Also, active writing is more concise, and concise writing is more vigorous.

Passive writing is remote, longer, sometimes ambiguous and readers can easily disengage.

That said, you might not want every sentence to be hard hitting. There’s a place for the passive voice. For example, in crime writing it can be very useful. Also, evasive characters might speak in the passive voice. But use it purposefully. Be aware of why you’re choosing the passive voice rather than accidentally falling into it.

When To Use the Passive Voice

Converting sentences to active voice

Look for at the word by (e.g. The Nobel Peace Prize was won by…). Rewrite the sentence so that the clause after by is closer to the beginning of the sentence so it becomes the focus. If the subject of the sentence is fuzzy, use a general term.

Grammar is the rules or conventions that make the meaning of language and sentences clear.

Grammar is the rules or conventions that make the meaning of language and sentences clear.

Many people don’t care about grammar these days. But writing in a clear way by observing these conventions will help you to convey your message most effectively and optimally. The correct use of grammar will also that can help lift your writing into the professional realm, letting people know you’re a serious writer who works at their craft.

There will be times when you want to break the rules of grammar in the name of creativity. Go for it! But it helps to know them first before working out how best to manipulate them.

The five books I find most useful for grammar questions are as follows:

To quote Winston S Churchill again, ‘This is the type of arrant pedantry up with which I will not put.’

All the writing talent in the world is meaningless if you don’t stay the course. You must apply ‘bum glue’ to adhere you to the process of producing work, consistently, relentlessly and unconditionally.

For many people, writing is hard and good writing—where readers are inspired to read on and recommend your work to others—is even harder. Often there are few rewards, at least initially. Yet most of us are conditioned, through education and parenting, to expect benefits for our efforts. With writing, we may need to endure years without recognition, remuneration or reward.

At times, the process becomes mired in negativity. For example, submitting work to agents and publishers often results in rejection. Even if you don’t submit to agents and publishers and self-publish, there’s no guarantee your e-book will sell. There are days too when you realise that despite your efforts, your work isn’t where you want it to be.

The hardest times, or crises, are often turning points that shape your writing self. But how do you keep going when you feel like giving up? The answer is through rabid determination. Here are some specific ways that might help:

In the words of Winston S Churchill:

‘Never give in. Never give in. Never, never, never, never—in nothing, great or small, large or petty—never give in, except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force. Never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.’

If you’re to succeed in writing—if success means writing your best story—then direct feedback (otherwise known as criticism) is invaluable, essential even.

But it’s a tricky thing. No matter how motivated you are to improve your work, criticism is by definition judgemental and aims to find fault (in the pursuit of improvement).

Here are some tips to surviving feedback or criticism, without losing the will to write. Above all, remember no work will ever be perfect and all criticism is subjective:

You could go on improving your story forever, so there’ll come a time when you’ll have to publish, in whatever form you choose. That way you can move on to the next story. We learn to write each story, and each one requires different tools, and so we continue along the learning trajectory—or is it cycle?—of writing.

Back story is difficult. It’s essentially what the writer wants you to know about their character – the who and why – but what the character them self doesn’t get the opportunity to tell you.

Some writers and editors say cut it out altogether because it’s telling (not showing) and interrupts the flow of your story by taking readers out of the action.

I’m not of that view, but if you’re going to use it, here are some ideas on how to make it most effective:

I’m off to cull and disperse more backstory in my MS. Good luck!

For whatever reason you’ve had a break from writing. Perhaps life happened, you had a holiday, you felt burnt out or were just sick of your own words. Writing breaks can be good as they can:

But how do you get back into it? The page seems daunting. You re-read what you wrote before and you aren’t sure if you can write that well again (It was a fluke. Not!). Or perhaps you don’t like what you wrote and it hits you that there’s more rewriting to be done.

Here are some ways to get back into it:

Don’t forget to have fun. You write for a reason, because you want to, you need to. Remember and honour that.

Some of mine off the top of my head include:

Some of mine off the top of my head include:

Should you write multiple books at the same time? Perhaps you have ideas and characters bursting out of you. Or you have two or more stories of equal importance.

I believe it’s possible under some circumstances to write two manuscripts at the same time, but with some clear boundaries.

That said, there are circumstances where your writing energy would be better spent getting one project to a certain finished point first. How do you know?

If you can’t stop yourself from writing more than one book at a time, here are some guidelines:

But if like many people working on two manuscripts means you’re diffusing your energy, there are ways you can keep your non-priority project alive.

Good luck fellow writers. Remember, never never never give in. Keep on learning and improving.

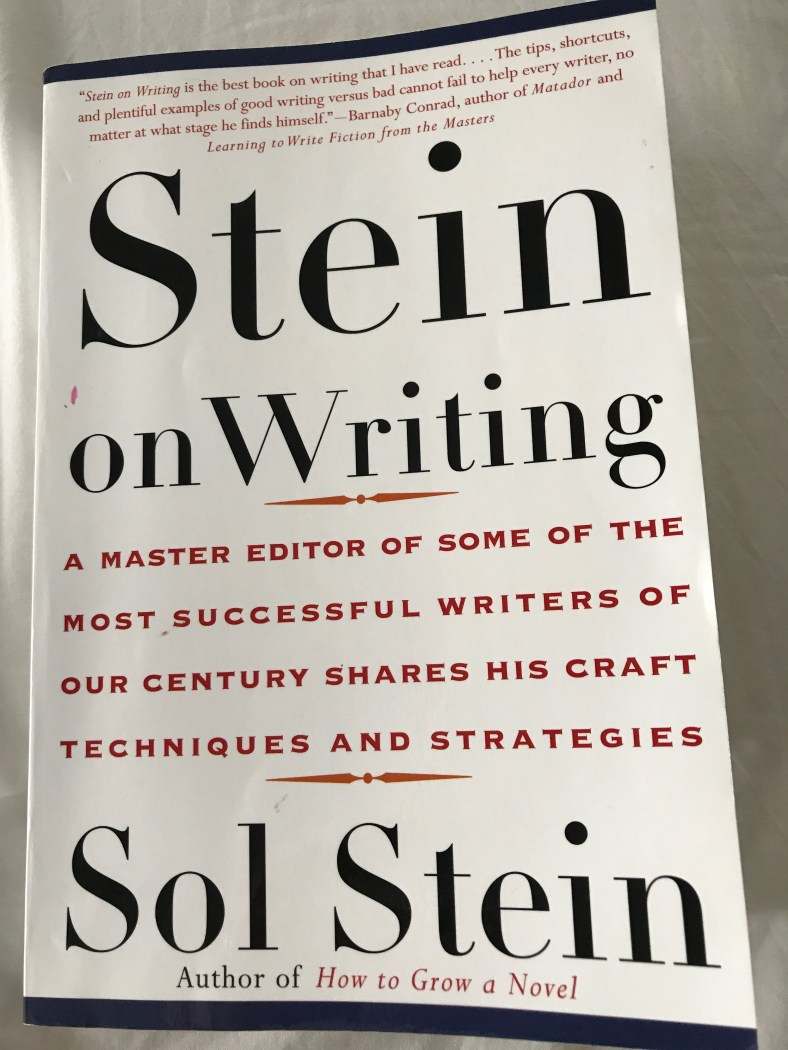

This how-to writing book was first published in 1995 but it’s my latest writing book read. Stein is a successful author and respected editor. While it’s a little outdated on the state of the book market, it’s a standout in its genre because it’s practical, technical as well as strategic, well written and inspiring. Stein also covers fiction and non-fiction, while many books do one or the other.

The topics he covers include the technical essentials such as character, point of view, opening, dialogue and how to stand out, albeit in a more strategic way than I’ve seen before (by that I mean he writes about these issues as part of the whole rather than as distinct aspects).

He also offers some different and more strategic approaches such as how to use all of the six senses in your writing, particularity, resonance, love scenes, tapping into your originality, ‘guts’ ad how to revise fiction. His great writing, frequent use of examples, and strategic point of view, and all done in an encouraging way, are memorable. I’ll always find his lessons useful.

Key take outs:

Score: 10/10 Instructive